Abstract – In prior studies of the world’s Stone Age geometric patterns, the author has claimed that the there is a subset of lines (which are found in ancient religious and astronomical sites) that exhibit common features, and these common features argue the lines are an ancient encoded text. In the author’s theory it is proposed that the hidden meaning that is contained in these lines is the angle of the line reflects specific astronomical values, and when these lines was used as an early alphabet, the direction of the line was used to represent the sound of the consonant, and the direction of the line was used to add a vowel to the consonant. It is thus proposed that the oldest alphabet was very similar to the modern day Japanese Hiragana and Katakana alphabets, but each charter was created with just one line. Obviously, the claim that Stone Age people could read has been met with resistance, from the archaeological community; and today most archaeologists are of the opinion that almost all the ancient patterns found in various Stone Age settings are just random doodles, and they also argue that if these ancient patterns show common repetitions in their angles, this is only because there was perhaps experimental bias in the prior studies. In order to answer this criticism, a new study was undertaken, in which the aim was remove any potential experimental bias from the study. This was partially done in prior work, but in this study it was decided to combine all the prior data from archaic geometrical patterns into one single study. In this study the patterns were also divided into two independent groups, in which one group involved the larger images which being so large they were fixed in orientation and could not be rotated, and to then compare the angles present in these large fixed geometric patterns against the angles present in much smaller geometric patterns which could be picked up and rotated. Using statistics, it is thus found that the probability p-value for the two datasets to be identical by chance is extremely low at p = 4.56×10-40, which is far less than p= .05 cut-off that is normally used to determine if a result is statistically significant. In fact, with this low value, the probability for these Stone Age lines being just random doodles is so low, it is more probable that on the very first try a person could toss a coin eleven times in the air, with the intent being the coin should land on its side, every single time. This means it is now reasonable to argue the currently accepted Null Theory (which states all Stone Age lines must be random patterns) is disproven; and it is now more reasonable to say these archaic patterns were constructed with deliberate intent. This is important because the presence of deliberate intent in such old markings can only suggests these marks hel meaning, and when contextual meaning is present in a written mark, it can then only be argued the marks must be a form of text. It is also observed that the angles present in these lines are consistent with astronomical values, with the five most common anglers being linked to the astronomical values that astronomers use to measure time and and predict solar and lunar eclipses.

Author: Derek Cunningham

Introduction

Are Paleolithic-era geometric patterns an archaic means to communicate through mathematics and astronomy, in which the angles drawn by the lines mark the astronomical values that are central to measuring time1,2; or are they a form of “pictorial writing with as yet uncertain meaning”3,4; or are they, as most would contend, just random childish doodles, with no true meaning5-13.

In order to test this first theory, which argues the oldest linear images were designed deliberately, and were linked to the measurement of astronomical values1,2,14, a statistical test was developed by the author, in which images of ancient geometrical images (from different eras and geographical locations) were divided into two independent groups. In the first group, a graph was compiled from all the angles observed in large static images, these being the angles extracted from large geometrical images present on the walls of caves; on walls of large buildings such as temples, or on other objects that are far too large to be rotated by any reasonable hand. In the second group, which is also identified as being the biased group, a similar graph was then obtained for all the angles present in portable art1,2,14,15; with the angles determined by best attempts to align as many angles to the most common angles seen in the static sample.

By dividing ancient images in this way, it is now reasonable to predict that if the Null Hypothesis is correct, and these ancient patterns are random, and various unconnected people drew them separately as artistic doodles or as simple artistic patterns, there should be no overlap between the data obtained from these two separate groups, other than that forced by the preliminary bias to force the top most common lines to overlap. However, if the data from these two groups are reasonably identical, which means the calculated p-value is less than .05, after the biased peaks are removed, it can then be argued that the angles present in these lines were designed to hold meaning (in other words, they were created with deliberate intent), and if that is the case they must then be considered the earliest known texts.

Experimental Background

Though many have long believed it would be very difficult, if not impossible to develop a mathematical test, that could determine the intent behind Stone Age art, in this case it can be argued if the ancient images are based on astronomy, then because astronomy is linked to mathematics, then the nature of the angles present within the images should also be linked to mathematics, and thus we should be able to reveal if these early geometric images were designed to contain astronomical context and meaning1,2.

In the astronomical theory, it is proposed that because earliest Stone Age era astronomers had no systematic method to record their observations (in the earliest days they had no written text) they would have struggled to record their observations. This means, the earliest astronomers would need to be inventive, and to start marking observations down by making lines. After a while, any series of single lines would start to become confusing, especially if the astronomer was observing different events in the night sky. Therefore, just perhaps, someone may have chosen to simply convert their astronomical values to a series of simple lines at different angles, with the angles used to identify the observation being made. In other words, it was just a simple code. A type of shorthand, in which the astronomical value could recorded by the angle at which the line was drawn.

This link to angles is reasonable, because many observation in astronomy are closely linked to changes in the angles, such as the angle between the horizon and the object (the moon, or a specific star) being studied.

However, it is clear that the amount of information that can be stored in this simple code is limited. Thus, over time, there would be a motivation to improve upon these earliest symbols, and it is proposed that these early astronomers chose to modify this simple system, to create a more advanced basic alphabet.

In this advanced, but to our eyes still painfully simple alphabet, the scribe would set a phonetic sound to the angle of the line2. But that alone would still limit the structure of the alphabet and it would still not generate enough useful sounds, especially if you wanted to create a functional alphabet. Thus a second modification made, and this modification made use of the fact the lines were offset as angles, to above and below, and to the left and right of the x and y axes2.

Because dividing angular offsets to above and below, and to the left and right of the x and y axes has the effect of restricting the angular values present in an images to between 1 to 45° (the lines to the left of vertical will overlap with lines aligned to above the horizontal at 45 degrees), this now limits the range of astronomical values that one could be recorded by this system.

However, the major advantage that offsets this limit is this now allows the four different directions to reflect the sound of four vowels a/o, e, u and i.

In this way, the angle of the line can now be given a specific consonant, such as s, g, n, or p, and now the direction that the line was offset to can now be linked directly to a vowel.

With these vowels attached directly to the consonant, this creates an alphabet that is very similar to the Hiragana and Katakana alphabets, which are two alphabets used today in modern Japanese. In Japanese the consonant K is never pronounced alone, but is alwos pronounced with a linked vowel, such as Ka, Ki, Ku, Ke or Ko. Here the difference between the modern Japanese alphabet and the proposed Stone Age alphabet is the Stone Age alphabet has one less vowel sound.

However, despite this restriction, in this very simple way just eight lines can be used to create a 32-letter alphabet2, and this is more than sufficient to create a written language. With five lines (equally spaced in each 45 degree block) there would be 20 letters, which would also be more than sufficient for basic communication. The proposed alphabet and the phonetic values, which were extracted from the study of a unique Chinese astronomical tablet , is shown below.

In this current statistical study, the assignment of which phonetic elements are attached to which lines1,2, will not be reviewed (see the above video).

Instead, the aim is to only determine if the angles present in these archaic geometric images do, as claimed, repeat in a consistent manner, and whether this consistent pattern does appears in all regions around the world.

This first question is important, because if these ancient geometric patterns fail to align in a consistent manner to the angles that have been previously claimed by the author to be critical to the theory, it would then follow that there can be no link to the proposed syllabic alphabet; and if there is no link, then all other connected arguments the author has made would fail. This is thus a very important test, and failure here would entirely nullify all the author’s prior studies.

As stated at the beginning, within this test, the geometric images are divided into two independent groups, and then the angular distributions contained within each group will be reviewed to determine if the results are statistically identical.

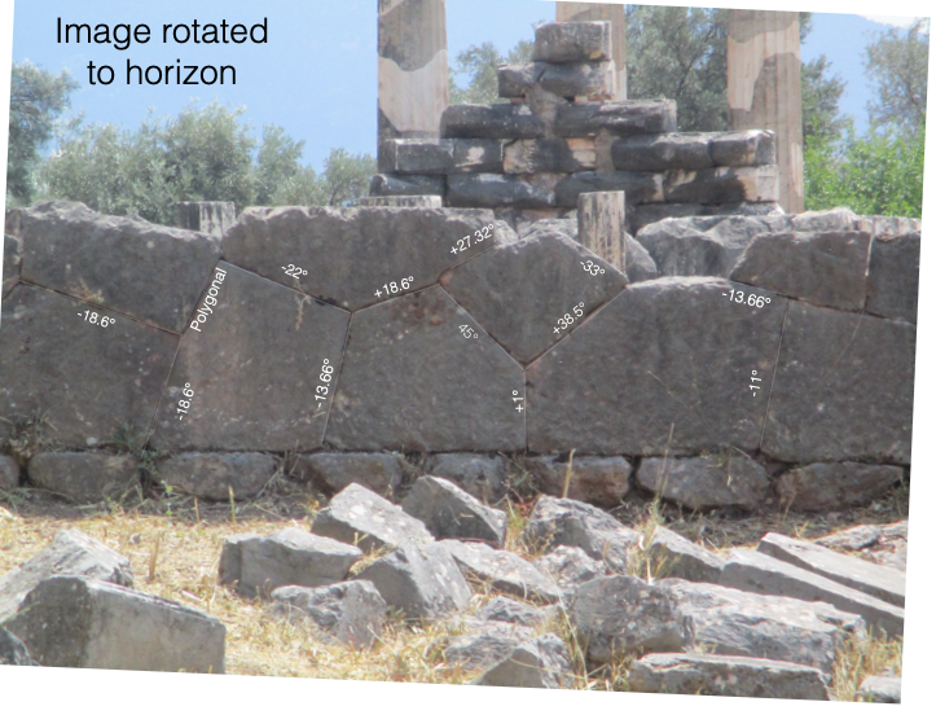

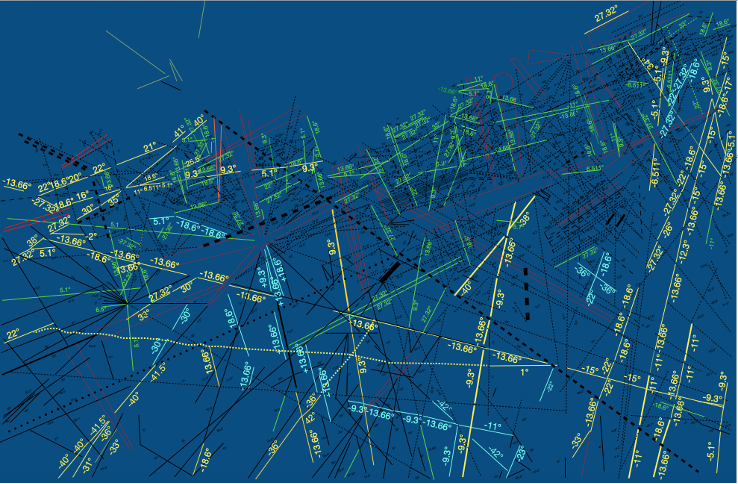

An image of one of the static, fixed geometric patterns (which cannot be rotated (except by a small amount to account for the movement of the Earth due to earthquakes) is shown below. This specific image was taken by the author, and it is from the Temple of Athena in Delphi, Greece.

As can be seen, after the structure is rotated so that the wall is now horizontal, and the pillars of the temple are upright, the angles present in the lines formed by the polygonal walls can be compared to a specific set of astronomical values.

In this example some of the lines (the lines set to plus and to minus 18.6 degrees, which represents the 18.6 year lunar cycle) are consistent with the proposed theory, and there does appear to be the presence of four-fold symmetry in the image, with again the lines aligned to above and below the horizontal and to the left and right of vertical. A similar trend is also observed in the lines set to circa 13.66 degrees, which in this model is a value linked to the half-sidereal month. The full duration of the sidereal month is 27.32 days, which appears in one line within this relatively small image.

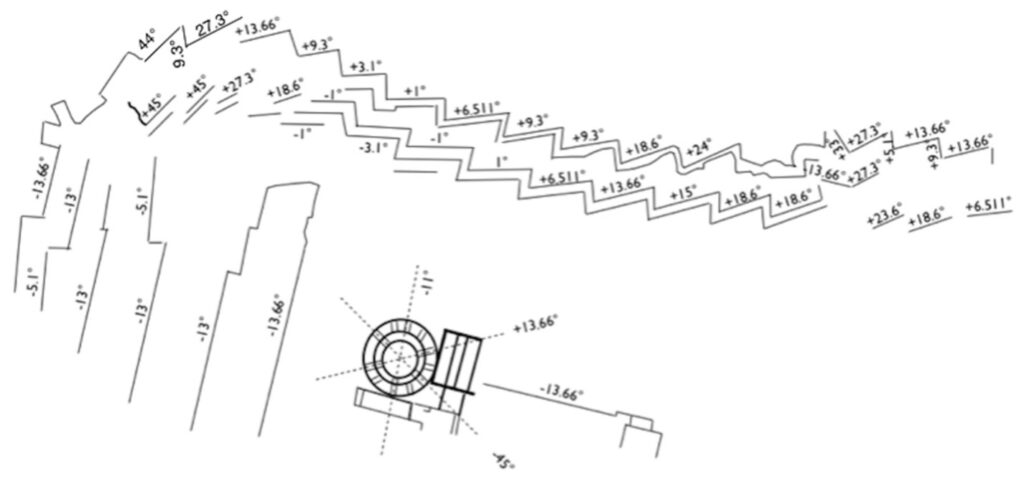

Other examples of geometric patterns that cannot be rotated are below the ground lines present at Nazca in Peru, and the layout of the polygonal walls at Saksaywaman Temple, which is also within Peru. As can be seen in the image below, the ability to reconstruct these images using the same limited range of angular values is again apparent. The structure of the oldest lines present in the Nazca lines will be discussed separately in a later paper.

Turning now to portable images, for this experiment, it is important to note that for these smaller, portable images there is no obvious marker in any of the obtained images that could permit an independent observer to determine what was the original orientation used during construction of the image. In fact, many portable geometrics appear to have been deliberately destroyed after they were made, and all we are left with (in most cases) are small fragments. This problem was also noted by Peter Underhill in 201316 a researcher in anthropology at Stanford University, in early discussions with the author. This means that, for the images present in this portable group, there is the need for trial and error, to determine what might be the best orientation for the remaining image, and due to this problem, this is where experimental bias will always occur. This is why care is required in constructing the experiment so that it is possible to remove this bias from the final analysis.

In this case, the first step was to repeatedly rotate and reanalyse the final results for each rotation compared, until it was determined that a best match was obtained.

The bias is then removed, in this experiment, by next arguing that this inherent bias should only affect, at most, the three most common angles measured. This is because, on average, the optimisation only involved looking at, at most, the three most common values.

Thus, if the data from the three most commonly observed angles is removed. Then all the other remaining angles should be random, if the Null Theory is true.

But, if the remaining lines do consistently match the data observed from the fixed orientation sample, then it can only be argued that the Null Hypothesis, cannot be true, and the lines must have context and meaning.

Finally, before looking at the data, except for where it is specifically noted in the text, all results have previously been published by the author, and their distributions cannot be changed1,2. This acts as a barrier, to prevent any secondary bias from entering the experiment, which might be caused by an attempt to reanalyse the various datasets after the fact. The analysis was also limited to images that had previously been published by museums, or those which had previously been published in science journals, or from images where the published data could be reasonably confirmed. In general, this means the photograph should be recorded with the camera perpendicular to the geometric pattern. However, because, in almost all cases, the distance to the image and the type of camera lens used in taking the photographs was not recorded by the archaeologists, only the central part of each image could be considered to be reliable. With respect to the experiment, this issue actually favours the Null Hypothesis, as it introduces a degree of randomness into the observed pattern, which should make it impossible to see an overlap between the two datasets.

It should also be again noted that in the author’s prior studies1,2 there is no claim that any of these archaic images were constructed to an accuracy of 1/10th, or 1/100th of a degree, such that the 27.32 day sidereal month must be recorded by a line that must be drawn exactly, at 27.32 degrees. That accuracy would be impossible to achieve in ancient geometric images. The only claim that is made is the angles created by the lines in geometric patterns can reasonably be reconstructed by a specific, limited range of pre-selected astronomical values. In terms of accuracy, the best remaining images exhibited an accuracy of ±0.1 degrees, while in the poorest quality images the accuracy of some lines could reach ±1 degree (typically when the error exceeded 0.5 degrees the lines were omitted from the study).

The list of geometric images considered to be portable include; from China, an engraved pattern on a circa 5,500 year old Jade block from Lingjiatan, which is known by Chinese historians as the earliest pictorial Chinese description of Heaven and Earth (this early geometric item, with a known contextual meaning, is from the National Museum of China collection in Gansu; a 5,500 year old Jade “Eagle that is marked by a central geometrical pattern that is considered to be an early representation of the sun17; from the Shuangdun, Bengbu site, four geometric images found on plates 92T0722(28):40; 92T0722(29):51; 91T0819(19):171; and 92T0721(29):3618; two circa 5,000 year old marked axe head fragments from the Liangzhu archaeological site that exhibit linear marks that some have previously argued are consistent with very early Chinese texts19; a geometrical pattern drawn on a Qijia culture Bronze mirror that is dated to circa 4000 year old; the linear early Chinese texts found on Oracle Bone R044284, which was recovered in Pit YH127 from The Ruins of Yin20; and a 14,000 year old marked stone from Pit 1 of the Shuidonggou archaeological site21; from Germany two circa 350,000 year old marked elephant tibia from the Bilzingsleben archaeological site22; from the UK, the lines drawn by the Bush Barrow Gold Lozenge23, the lines present on the Stone of Scone (for this study a detailed image was obtained from Historic Environment Scotland), and the lines found on a statue called the Orkney Venus; from the Czech Republic the circa 30,000 year old Dolní Věstonice wolf bone; from the Meuse Basin in Belgium the Remouchamps bone, which is believed to be between 10,000 to 12,000 years old24; from Patne, in India the linear pattern drawn on an engraved egg9; from Africa a multi-lined star type image drawn by the San Bushmen25; from the Democratic Republic of Congo the circa 20,000 year old Ishango Bone, this bone has marks that the late Alexander Marshack, of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology identified as representing a 6 month calendar; and from South Africa the linear pattern found on two engraved eggs from the Diepkloof Rock Shelter collection26,27; a marked stone recovered from the Wonderwerk Cave, and a marked pebble also recovered from the Wonderwerk Cave10,28; a marked stone from Klein Kliphuis29, a marked stone from Klasies River Cave; and three circa 70,000 to 100,000 year old engraved stones recovered from Blombos Cave, these being identified as Blombos M3-1, M1-5, and M1-6 from the studies undertaken by d’Errico, Henshilwood and Nielsen30-32; and from the Lebombo-Border Cave a marked, circa 43,000 to 44,200 years old Baboon fibula (this was discovered in the 1970s by Peter Beaumont, who later identified the markings as being an early lunar count); and two 24,000 year old Lebombo (Border) Cave notched wooden sticks, which have been identified to be coated with poison31,32. See Cunningham1,2 for the prior studies and the angles present in each of these samples.

The fixed-orientation patterns are; from Peru the Nazca ground lines from all eras of its construction (see Fig. 2), and the angular distribution drawn by the polygonal walls at Sacsayhuamán relative to the cardinal axes (Fig. 3); from the UK, the angle between neighboring Aubrey Holes, Y Holes, and Z Holes at Stonehenge (see again Cunningham 2012 and 2018); from Greece the angular distribution observed by the various walls within the Acropolis relative to the cardinal directions; and from France the angles present in the geometrical images found at Lascaux Cave, these were recorded by the Musée d’Archéologie Nationale, as part of the ongoing attempt to record and preserve the various Lascaux images.

Also considered to have a fixed-orientation but the images were permitted a small degree of rotation, to account for ground movement, or small potential errors in camera alignment are; from Delphi in Greece the Polygonal wall under the Temple of Apollo, and the polygonal Wall in front of the Sanctuary of Athena33; in Athens a short polygonal wall found at the base of the Temple of Hephaestus in Agora34; in Australia the various geometric patterns found at Carnarvon site, and the geometric images found at the Perminghama Petroglyphs; in America the Anasazi Ridge petroglyphs, and the V-bar-V petroglyphs located in the Sedona Red Rock region; from Tibet a Mascoid with the image supplied from the collection of John Bellezza; from Egypt the linear pattern surrounding an image called the spider, which was found on a wall at the Kharga Oasis; and finally from Hawaii the Olowalu Petroglyphs.

Results & Discussion

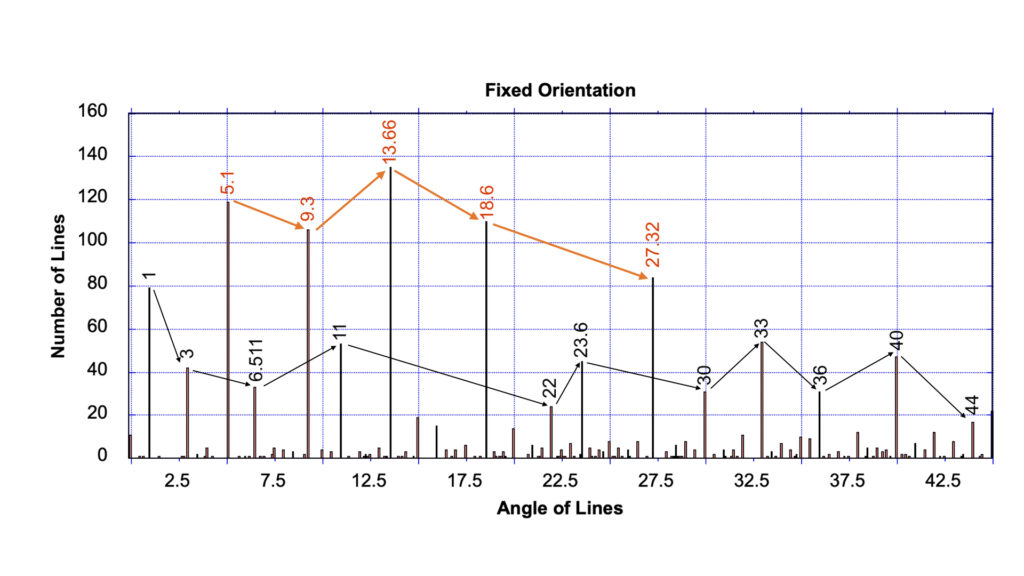

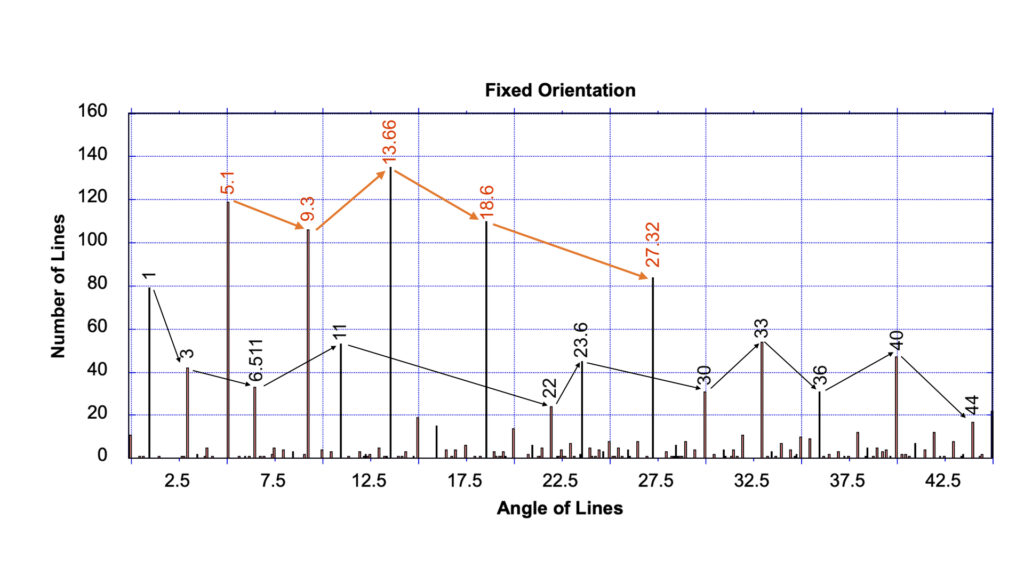

In the geometric patterns that are fixed in their orientation (see again Fig. 1 to 3 for examples), five angles dominate. This is shown in Fig 4a. In total 1432 lines were analyzed in the fixed-orientation group. and the data for the fixed orientation group is shown directly above the data from the portable “art” group to assist with comparison.

click on image to enlarge

As can be seen, the five most common alignments are lines at circa 5.1 degrees; at 9.3 degrees and 18.6 degrees (which are angles that correspond to the half and full 18.6 year lunar cycle); and at 13.66 and 27.32 degrees (which corresponds to the half and full sidereal month). In the proposed, Null-Hypothesis (the Null Hypothesis being the current Random Line Hypothesis) it was argued that these five angles should not be highlighted just by chance, as the dominant group.

In total 119 lines appear at circa 5.1 degrees (which is equivalent to 8.31% of all lines studied in the fixed-orientation class), there are 106 lines at circa 9.3 degrees, 110 lines at circa 18.6 degrees, 135 lines at circa 13.66 degrees, and 84 lines at 27.32 degrees. These numbers are between 2.6 times to 4.2 times more frequent than expected for a random array.

Though 878 lines (61.31% of the total) could be considered to be randomly aligned, it was found that amongst there 878 lines 685 of these lines were from just one site, the Nazca site, which was by far the largest site studied.

Because the Nazca lines contribute so many lines to the fixed-orientation study, a more detailed analysis of the Nazca lines was undertaken; and from this it was found that not all the lines at Nazca are equivalent. For example, from photographs of the actual lines there are 102 lines that appear to be dashed, and 28 lines that appear to be now used as small tourist paths and they are not usually included in the study of Nazca, mainly because they are thought to be trails. Within these two lesser studied groups 55 (53.9%) of the dashed lines and 20 (71.4%) of the “path” lines were found to be consistent with the proposed angular theory. This contrasts with only a meager 160 of the more prominent (and more famous) lines matching the proposed theory (this being only 23.4% in this group).

When compared to the other geometric images from the fixed-orientation group (see Table 1 and 2), the data from the Nazca “famous” lines was found to be an outlier1,2.

The next sample, also with a poor overlap, is the Olowalu Petroglyphs which are found in Hawaii. This only had a 30.51% to the proposed alphabet theory, and Carnarvon came in at 47.06% See Cunningham1,2 for source data.

However, all other images studies, (of which there were many) revealed that more than 50% of their lines are aligned to just these five specific angles. This seems to suggest the famous Nazca site was constructed in two, or perhaps three distinct stages, with the most prominent pattern (which is the pattern that shows the lowest match to the proposed astronomical-alignment theory) being perhaps the most recent stage in the development of the Nazca pattern.

Amongst the other angular values present, the sixth most common angle occurs at circa 1 degree, with 79 lines (or 5.52%) aligned to this angle. This is then followed by four lines that are aligned to circa 11, 23.6, 33, and 40 degrees, which each have between circa 45 to 55 lines. These secondary values, with the exception of the 40-degree line, can all be easily assigned astronomical meanings.

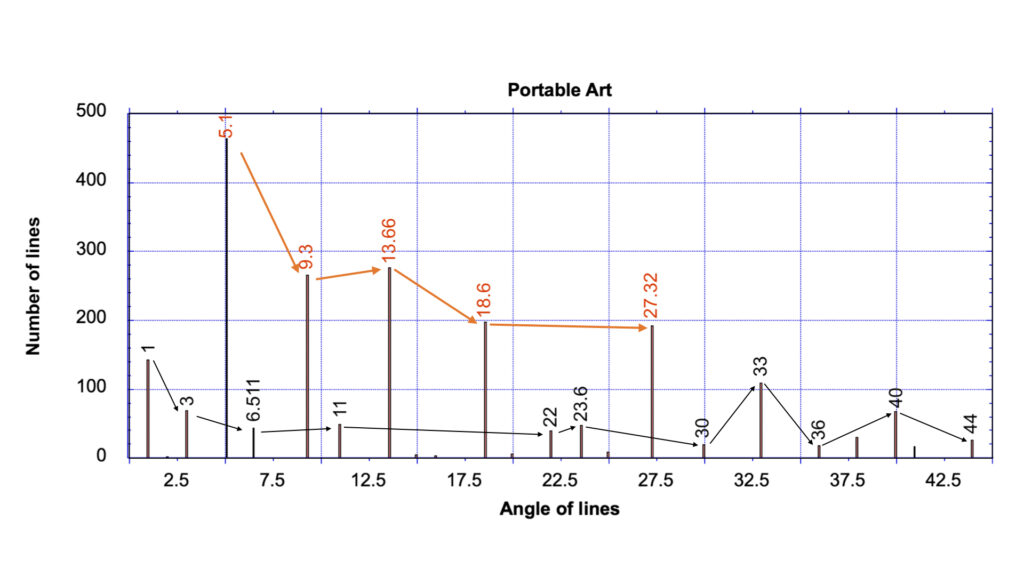

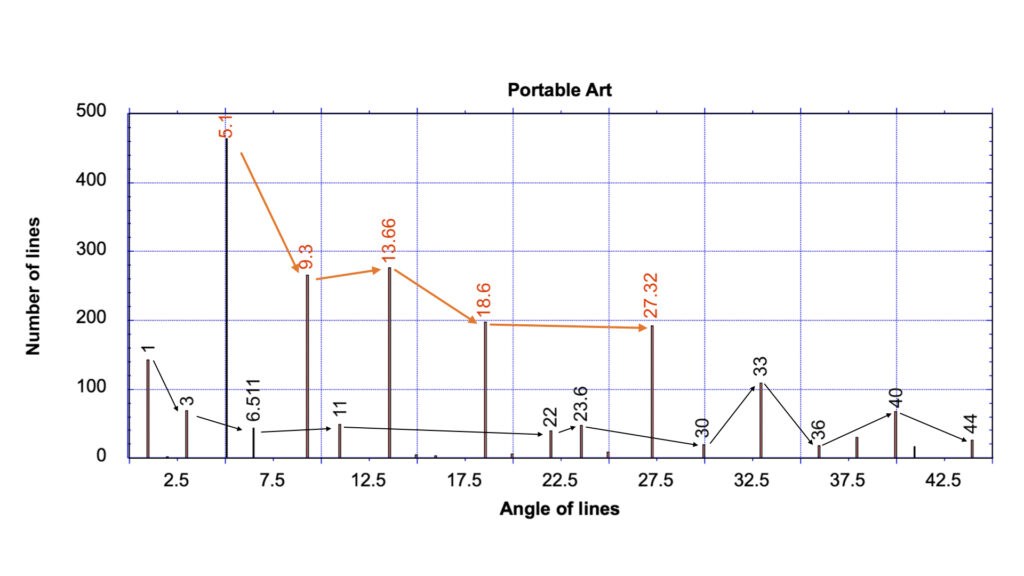

Turning now to the results from hand-portable samples, there were 2106 analyzable lines in this group (see Fig. 4b).

The most obvious result is despite the prior concerns over lens-induced, image distortion, which had the potential to swing the data in favor of the Null Hypothesis, the exact same five lines were still found to dominate; with the highest frequencies occurring within the angular distribution at circa 5.1, 9.3, 18.6, 13.66 and 27.32 degrees.

Within the study of portable images, there are 464 lines at 5.1 degrees, 266 lines at circa 9.3 degrees, 198 lines at circa 18.6 degrees, 277 lines at circa 13.66 degrees, and 192 lines at circa 27.32 degrees. These numbers are between 4.14 times to 10.02 times more frequent than that expected for a random array.

To compare these two datasets, using statistics, the first step was to calculate the number of possible combinations that can arise from 45 isolated peaks (each with a base accuracy of circa ±0.5°); and to then determine the statistical probability that the same pre-selected group of five angles (which were pre-chosen for their astronomical significance) will dominate, in both the fixed-orientation study and the portable-geometric study.

From combination statistics, this is a straightforward calculation, and it can be calculated to be equivalent to a 1 in 1,221,759 chance (from 45C5). This, in probability terms is equivalent to a p value, of 8.2 x 10-7, where a p value of .01 represents a 1 percent chance that the lines are random. A value of 1 would indicate it is 100% certain that the lines are random, and in medical trials a p-value of .05 is the standard value used to mark a clinical trial as being successful or statistically significant. As can be seen the value in this specific test is well below this boundary.

However, this is not the final p value. This is because the 8.2 x 10-7 p value does not take into account the requirement that the same angles were drawn along four separate directions (that is the lines are offsets to above and below the horizontal and to the left and the right of vertical).

In this case, these four directions can be considered to be four independent datasets. Thus, it is more accurate to say that the probability for these five lines to dominate in the fixed-orientation in all four directions is actually 1 in 2.2 x 1024, which is equivalent to a p value of 4.49 x 10-25.

As this p value is exceptionally low, this value can already be used to argue that that these geometric lines were drawn, intentionally, to these specific angles, and the lines are not random.

But there is another parameter that must be included. The calculation of the final p value must also look at the common overlap that can be seen between the portable-and fixed orientation images. These being the two independent studies that were considered crucial for removing bias from the analysis of the portable “art” images. (see Fig 4a and 4b).

click on image to enlarge

Because the portable sample involved a pre-selection process, which, for the purpose of this statistical study is assumed to have pre-chosen three of the five primary peaks observed (note this is actually a high estimate, because in reality the process for aligning portable images usually only employed two of the five peaks in the optimization step), this means, for the portable image study, it is only necessary to calculate the probability that just the last two (out of five) peaks will, by chance, match the proposed five-member series.

This means, in the portable image study, the combination statistics is calculated from 45C2, which is equivalent to a 1 in 990 probability for a single angular range.

In terms of probability this generates a p value of .001, which marks this results alone as being statistically significant, but when this is again modified by the fact the same angles appear in four independent directions, the final probability for this overlap to occur in the portable study is just 1 in 9.6 x 1011. This equals a p-value of 1.04×10-12.

When the combined p value is calculated for the two independent studies overlapping, the calculated p value is then 4.67×10-37, but this is still not the final p value. This is because, as mentioned earlier, this study is not limited to just five peaks. In this specific study, the interest is in the behaviour of the 16 most common peaks, these being the values considered to be either linked to astronomy, or to geometry, or are seen in above average numbers in prior studies of these ancient geometric patterns1,2.

As can be seen here, the various peaks do have different numerical frequencies, but what was unexpected is the manner in which they vary, (see again Fig. 4a and 4b).

The unexpected result, and this is the first time that this feature has been observed is the two independent studies show a long, extended series of common increases and decreases, between the various primary and secondary peaks. In total there are four common variations in the five primary peaks and there are ten common increases and decreases between the eleven secondary peaks that were recorded.

The mathematical relationship between the peaks has been discussed in previous studies by the author, in terms of astronomy, but in terms of phonetics, these common oscillations now appear consistent with standard linguistic theory, which argues some letters (or sounds) will appear more often than others, in both the spoken and written languages.

In terms of statistics, the probability for this similar repetition to occur in the sequential magnitudes is just 1 in 1,048,576, this being calculated for the 10 common increases and decreases in numerical frequency amongst the secondary angular values; which means, when this probability is combined with the other prior statistical odds, the p-value for these images being random now drops to just 4.45×10-43. If the analysis is extended to include the 5 most common peaks the probability reduces further to just 1 event in 9.2 x 1045, which is equivalent to a p-value of 1.08×10-46.

With the result being at this low magnitude, it was decided it had become unnecessary to further refine the data, as it is reasonable to round p-value of this magnitude to zero. In statistics this is rare, because a p value of zero implies the proposed alternative theory is proven, which in this case means the lines found in ancient geometric images were created with deliberate intent, and the Null Theory (which argues the lines are random) is disproven

Though this test does not use statistics to test the likelihood that these lines are linked to astronomy (as noted previously, this study only tests the probability that the lines are random), it is clear that there had to be an underlying motivation to create these lines to these specific values over such a long time period, and in so many different regions.

Because any conceivable motivations based on art are subject to change, people are driven to do new things and follow new fads, this argues that these archaic lines are based on observations that are fixed and unmovable, and it is clear, in this case, that these angular values do overlap with the values expressed by standard astronomical terms.

For example, the line at 11 degrees equals the 11 day difference between the lunar and solar year and the 33 degree value equals the 33-day reset value that is required to normalizes the lunar and solar year each three years, and the line at circa 23.6 degrees is equivalent to the angle of Earth’s axial tilt.

In addition, not only are the values consistent with basic astronomy, the proposed link to astronomy would give the motivation to use these values, unchanged, for thousands of years; because these values can be used by astronomers to predict lunar and solar eclipses. This is an ability that the astronomers and early politicians may have perhaps found useful; and this brings us to perhaps the most important observation.

The link to the story of the Tower of Babel is these astronomical images are found worldwide, and their appearance begin very early in what could be considered “modern” human history, with the three oldest studied geometric patterns being two circa 300,000 years old bones from the Bilzingsleben archaeological site, and one fixed-orientation image, of similar age, that is found on a wall at Rising Star Cave site, in Africa.

The intrigue is the Rising Star Cave is known to have been occupied by Homo naledi, but the same distributions in angular values can also be observed in sites that are linked to anatomically modern Homo sapiens; as well as within sites that were occupied by Homo heidelbergensis, and also by the Denisova hominins.

From this observation it is clear that further work is required, not only to determine who first made these ancient patterns, but to also determine if multiple species of human used the this archaic text at the same time.

References

-

- The Map That Talked, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, first published Nov 2012, current edition published 2018.

-

- The Babel Texts, CreateSpace Independent Publishing, 2018

-

- von Petzinger, Genevieve, First Signs: Unlocking the Mysteries of the World’s Oldest Symbols Published. 2017

-

- Von Petzinger., G., and Nowell, A., A place in time: Situating Chauvet within the long chronology of symbolic behavioral development, Journal of Human Evolution 74:37–54 (2014).

-

- Bandi, Hans-Georg

-

- The Art of the Stone Age Forty Thousand Years of Rock Art, H.G. Bandi ed. Introduction, Holle & CO Verlag, Baden-Baden, Germany, 1961.

-

- Breuil, Henri The Art of the Stone Age Forty Thousand Years of Rock Art. H.G. Bandi ed. Pp 21 Holle & CO Verlag, Baden-Baden, Germany 1961.

-

- Bednarik, Robert G., Creating Futile Iconographic Meanings. http://www.ifrao.com/creating-futile-iconographic-meanings/.

-

- Bednarik, Robert G., The Earliest Evidence of Palaeoart, Rock Art Research 2003 20(2):3-28.

-

- Bednarik, Robert G. and Beaumont, Peter., Pleistocene Engravings from Wonderwerk Cave, South Africa, Préhistoire, art et sociétés: bulletin de la Société Préhistorique de l’Ariège, 2010, Pp 96 ISSN 1954-5045, Nº. 65-66.

-

- Halverson, J., Art for Art’s Sake in the Paleolithic, Current Anthropology, 1987 Vol 28(1):63-89.

-

- Halverson, J., The first pictures: perceptual foundations of Paleolithic art, Perceptions 1992 21(3):389–404, (1992).

-

- Ucko, Peter J. and Rosenfeld, A., Palaeolithic Cave Art, (McGraw-Hill, New York. 1967.

-

- Researcher Suggests Famous Ancient Inca Monumental Complex Exhibits Astronomical Values, Popular Archaeology, April 2014 https://popular-archaeology.com/article/researcher-suggests-famous-ancient-inca-monumental-complex-exhibits-astronomical-values/.

-

- Researcher says evidence of astronomical writing etched into Cypriot artefacts, Cyprus Mail https://archive.cyprus-mail.com/2014/02/02/17933/ [accessed 2023].

-

- Underhill, Peter., 2012 In-person discussions, Stanford University.

-

- Lingjiatan Culture Research, 凌家滩文化研究, 文物出版社, Lingjiatan Culture Research, Cultural Relics Publishing House 2006 [in Chinese].

-

- Shuangdun, Bengbu, Neolithic Site at Shuangdun, Bengbu, Kaogu Xuebao 考古学报 (Acta Archaeologica Sinica), 2007, 1, Pp 92-126.

-

- CBS News release, 2013, https://www.nbcnews.com/sciencemain/5-000-year-old-primitive-writing-generates-debate-china-6c10610754.

-

- Museum of the Institute of History and Philology, Taiwan (2018). This specific Oracle Bone is currently stored in the Museum of the Institute of History and Philology, Taiwan.

-

- Personal communications with Shuidongou Site Director Fei Peng, March, 2018.

-

- Sachsen-Anhalt collection, Image obtained from the Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt collection, 2018.

-

- The image of the Bush Barrow Lozenge used in the 2018 study was obtained directly from David Dawson, Director, Wiltshire Museum Collection. It should be noted there are many images online which show reproductions of the Bush Barrow Lozenge, which differ in the angular distribution from the original.

-

- Demoulin, Alain, the source image used in Cunningham2 was obtained from Landscapes and Landforms of Belgium and Luxembourg, Pp 125, Springer.

-

- Lewis-Williams, David., The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art, 2004.

-

- Wong, Kate., Engraved Ostrich Eggshell Fragments Reveal 60,000-Year-Old Graphic Design Tradition, Scientific America, Volume 302, Issue 3, March 2 2010: Observations.

-

- Texier P-J, et al. A Howiesons Poort tradition of engraving ostrich eggshell containers dated to 60,000 years ago at Diepkloof Rock Shelter, South Africa. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107:6180-6185.

-

- Thackeray, Francis., Personal communication, March 2018. The pebble reported by Peter Beaumont and Robert Bednarik is said to have come from Unit 4, Excavation 1, at Wonderwerk Cave.

-

- Mackay, Alex; and Welz, Aara., Engraved ochre from a Middle Stone Age context at Klein Kliphuis in the Western Cape of South Africa, Journal of Archaeological Science 35(6):1521-1532, doi 10.1016/j.jas.2007.10.015.

-

- Henshilwood, Christopher and d’Errico, Francesco, Middle Stone Age Engravings and Their Significance to the Debate on the Emergence of Symbolic Material Culture, Homo Symbolicus: Dawn of Language, Imagination and Spirituality Pp75-96 C. Henshilwood, and F. d’Errico, Eds., John Benjamins, Amsterdam 2011.

-

- d’Erricoa, Francesco; Banksa William E.; Warrend, Dan L.; Sgubine, Giovanni; Niekerk, Karen van; Henshilwood, Christopher; Daniaue, Anne-Laure; and Goñie, María Fernanda Sánchez; Identifying early modern human ecological niche expansions and associated cultural dynamics in the South African Middle Stone Age, PNAS July 25, 2017(114(30)):7869–7876, doi:pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.1620752114.

-

- d’Errico, Francesco; Backwell, Lucinda; Villa, Paola; and Beaumont, Peter B; Early evidence of San material culture represented by organic artifacts from Border Cave, South Africa PNAS July 30, 2012 Vol. 109(33):13214-13219, doi:doi.org/10.1073/pnas.120421310.

-

- Author image, previously unpublished data.

- Author image, previously unpublished data..