Abstract – In prior studies the Lingjiatan Eagle was argued to describe the orbits of the planets, and through comparing the remnants of various ancient languages, an attempt was made to use the Jade pendant to reconstruct the the names of the planets, and determine the structure of the phonetics behind the Babel Texts. In this article the data surrounding the names of the planets is reviewed.

Introduction

It might seems obvious that the earliest astronomers would be aware that amongst the lights in the night sky there were five that moved. Yet, in the earliest known texts the planets are seldom mentioned.

Though it is often claimed that the planets are “mentioned” in some early Mesopotamian Tablets, there is one major problem. Some of the known translations of the Mesopotamian tablets appear to be incorrect1. For example, there are clear errors in the structure of the translated texts for the tablets that have been argued to describe the areas of squares and rectangles1, and these errors appears to cast substantial doubt on some of the other translations that are given to “mathematical” tablets1, and the reigns of the kings, and perhaps also the names given to the planets1, these being; Sin (the moon); Shamash (The Sun); Nebo (Mercury); Ishtar (Venus); Nergal (Mars); Merodach (Jupiter); and Ninip (Saturn).

According to Mathieu Ossendrijver, who used a reading for the astronomical relics linked to astronomy, the related Akkadian names for the moon and the five planets, from 1800–1000 BC, are Sin or Sinu (the moon); Samas (the sun); Šiḫṭu (Mercury); Dilbat (Venus); Ṣalbatānu (Mars); and Kayyāmānu (Saturn)2. No translation was given for the name of Jupiter. It should be noted that modern interpretations, which give the word Kayyamānu to mean Saturn, are based on really questionable interpretations of the texts which assume the planets were personified as gods, and thus certain words might be the ancient names for the gods, and thus working backwards the names of the planets. These modern names, which are now commonly seen in Wikipedia cannot be relied upon.

What is interesting in the oldest stories is the motion of the planets in the night sky were used to predict the onset of rain and changes in the weather. This link to water also appears within the oldest Vedic texts in India.

However, in this article the interest is in the names of the planets. Unfortunately, within the Bible, which is a religious book and not a book on weather, the names of the planets are not given. The Bible only mentions that the planets were known, but just like today, in modern text books, there would have been no reason to mention the names of the planets in a book on religion, if astronomy had become separated from the study of the night sky. For example in Jude 1:11-13 we find the passage,

Woe to them! For they walked in the way of Cain and abandoned themselves for the sake of gain to Balaam’s error and perished in Korah’s rebellion. These are hidden reefs at your love feasts, as they feast with you without fear, shepherds feeding themselves; waterless clouds, swept along by winds; fruitless trees in late autumn, twice dead, uprooted; wild waves of the sea, casting up the foam of their own shame; wandering stars, for whom the gloom of utter darkness has been reserved forever.

As can be seen, the planets are mentioned in passing, which confirms the ancient clearly did know about the planets, but within biblical texts the study of the night sky had no relevance to the study of god.

This separation was not maintained in India. However, within the Vedic text, Shatapatha Brahmana, even though it is often said the planet names are directly mentioned, in these texts the texts are actually only talking about the birth of the gods. It is only later in the late 19th century texts that the names of the gods start to begin to become associated the names of the planets. Whether these god-planet assignments are correct is totally unclear.

In the Aitreya Brahmana 3.34, (a Brahmana can be thought of as a scientific note to explain the preceding texts) the author referred to the sequential births of Aditya, the sun; which is then followed by Bhrgu, Venus; and Brhaspati, Jupiter. As can be seen the names differ substantially from the names given in the Akkadian texts and also the early Mesopotamian texts. Intriguingly, though the Akkaian and Mesopotamian texts do give identical names for the moon and the sun, the names for the planets differ. This again might be due to the translators of these texts ascribing, in error, the names of the gods to the names of the planets. This realm of the gods in ancient religions is discussed in more detail in “The Map That Talked., and at its most basic level, the evidence points to the gods being linked to the constellations (the Heavens), and how these constellations are mapped to the planet Earth.

For this reason, I find the work of David Frawley to perhaps be the most persuasive. Frawley noted that there was one other possibility for naming the planets from these ancient texts. In his studies he noted that, in the early Vedic records the sidereal month was able to “traverse the entire zodiac in 27.3 days (gandharvas?) “See (https://multifaiths.com/pdf/planets.pdf). This is important because the sidereal month is now known to be central to the structure of this ancient Stone Age Text (see the prior statistical study here). Frawley also argued that this astronomical sentence meant that each sidereal day the moon would moved and overlap a different constellation (a naksatras) in the night sky, and thus the later division of the night sky, which is mentioned in the Rg Veda texts, into 34 “lights” only appears to only make sense if the seven additional “lights” (27 plus the extras 7) were the five wandering stars, plus the moon and the sun.

The theory held by David Frawley was that the Atharva Veda (section XIX.6.7) just might name at least two of the planets starts with a passage that states

May the earthly and atmospheric powers be peaceful to us. May the planets (the graha) that move in Heaven give us peace.

source – David Frawley, Planets in the Vedic Literature

Thus it is known that this text does mention the planets were (as others have previously noted). It also notes the “atmospheric powers, which suggests the authors who wrote these texts were concerned about heavy rains and strong winds.

However, for this study, the more interesting section is where Frawley believes the planet names is contained in the texts that deals with religious offerings. Specifically, the text discusses the offering of various Śukra cups which held varying levels of water during the astronomical event that was being worshipped. For example, during the sidereal (or lunar synodic) months, the cups were emptied during the waning phase and the cups were filled as the object became brighter. Thus, it was argued by David Frawley that the names given to the Śukra (the cups used in the offering) just might be linked the names of astronomical object to which they were attached.

This logic seems reasonable. One could easily imagine an elder instructing a student to grab the Mars cup, or the cup for the moon. This means the word Agni (which is the name ascribed to the cup in the text) might be the original name given to Mars; and according to research scientist Subhash Kak4, the name of Venus might be Bhr.gu, or Kāvya or perhaps Kavi Uśanas. As can be seen, there remains substantial confusion, even amongst those who have studied these ancient texts extensively.

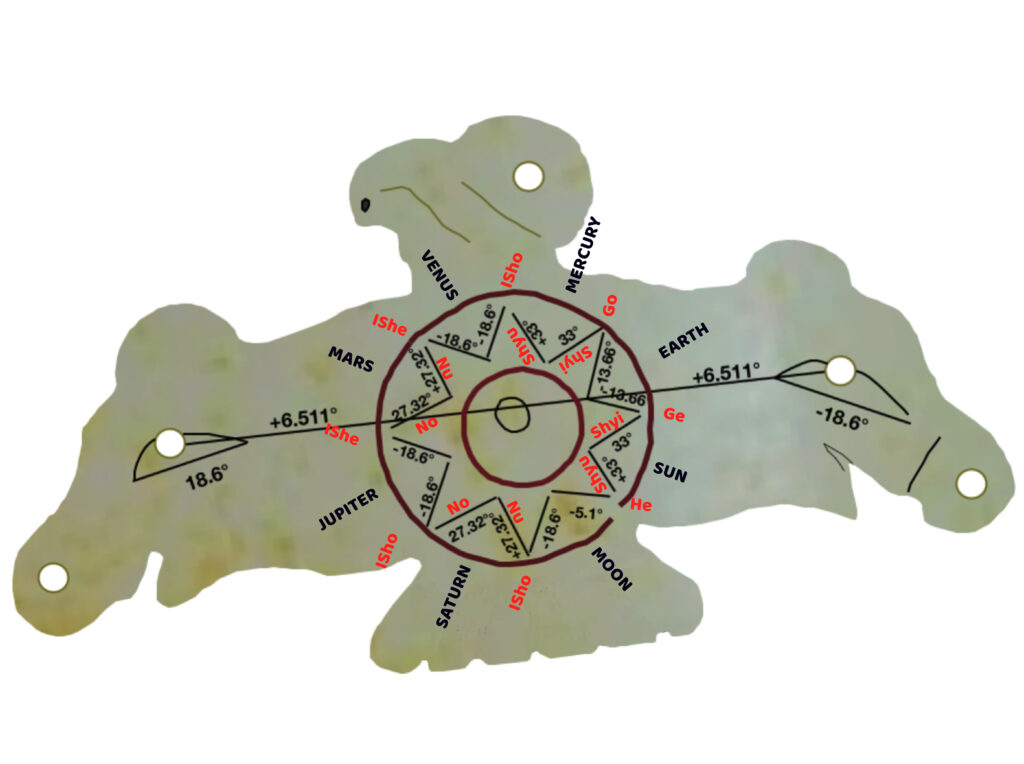

And at this point we now turn to the Chinese Lingjiatan Jade Eagle. Here the working theory is each line pair pointing inwards to the centre is linked to the names of the celestial objects.

With only two lines, and the working theory being that the angle of the line represents the sound of a vowel; and the direction of the line represents the sound of the vowel, it can be argued that the names of the planets on the Jade Eagle should be short and can be no longer than two “astronomical letters” long. For example the letter N needs to be paired with a vowel, thus the four possible directions would generate the “letters” Na, Nee/Nay, Nu and No; and the letter G the “letters” Ga, Gee/Gay, Gu and Go. With the lines being aligned to either above or below the horizontal, or to the right and left of vertical, there is no room to create five separate vowels, but with just five lines it is possible to create 20 phonetic letters, that would resemble the structure used in modern Hiragana and Katakana alphabets in Japan.

This argues that the only ancient names that can be considered are the short names such as SiNu, and NiNip.The This fits with the theory that as humans began to learn to speak there would be few spoken words, and most spoken words would be short, as there would be no need to make them more complicated.

As can be seen, the Lingjatan Jade Eagle, is dominated by the presence of a central eight-sided star.

This jade carving has been studied by many Chinese archaeologists and historians5, and it has also become famous worldwide.

Over the last few decades, Chinese archaeologists have recovered various examples of Jade Eagles at sites connected to the Hongshan Culture (红山后) in northeast China, and from the remains of the Longshan culture in north China. According to Xiaoman Huang and Cheng Wang5, “Almost all the eastern coastal areas of China are dominated by bird totems [and] China’s three prehistoric tribes [the] Huaxia, Dongyi and Miaoman [tribes], all had the custom of bird worship…”.

With the images of Birds and Suns being so common in Chinese archaeological finds, the Chinese archaeologists now routinely call these finds sun-bird artefacts, with Huang and Wang reasonably stating that later cultures then used these early limages to create the myths surrounding the Phoenix, the bird that is reborn from fire.

Within China, the eight-sided star symbol is first documented within the Chinese middle to late neolithic. Here it should be noted that because the neolithic definition depends on the nature of the objects recovered, different regions , even within the same country, may have different “neolithic periods”. In addition, the time period linked to the middle and late neolithic can also change by thousands of years as new finds are recovered in each area. This means the term “Neolithic”, though it is used often, is not an accurate term. At present the Lingjiatan Middle Neolithic runs from circa circa 5000 BC to 1700 BC.

Huang and Wang also mentioned in their studies that, the image of the 8-pointed star has mainly been recovered from the following regions; Dongting Lake, Yuan River, Haidai, Tai Lake and Chao Lake.

From the various finds recovered, the image of the octagonal star, in each area, is linked to specific materials, with the material used changing with region. For example, within the area surrounding Dongting Lake the star images appears mainly on white pottery, and in the Taihu Lake region it is mainly found on what appeared to be “spinning wheels” – this may reflect the idea that the image represented the orbits of the planets, and the planets “spin” around the stars. In the Haidai area they were recovered on painted pottery.

However, the most intriguing observation by Huang and Wang5 is that concerning the shape and structure of the star and circle, there is little difference between the various finds from the different regions. However, unfortunately, at this time, in my studies of the Chinese literature, I found it was difficult to located any reliable images of these other patterns, with the text simply stating the star symbol is often compared to the Anise seed (八角).

I also found one feature of the Jade Eagle, which I should have been aware of during my initial study of the Jade Eagle. Unfortunately, at that time my ability to translate Chinese was limited, and I did not realise that the Jade Eagle has the same image carved on the opposite side of the pendant.

In fact, the same pattern is almost identically on both sides.

I also admit that when I first studied this Jade Eagle, several years ago, I do remember seeing one isolated image of the rear side of the Jade Eagle, but at that time, because the two images were so similar, and I was also to seeing the reverse side of pendants from this time period being blank, I made a mistake and I thought that this was just a case of the image being reversed (being flipped horizontally). Sometimes, I have seen this done in youtube videos, where the “creator” will flip the video horizontally, in order to get around copyright issues, and I thought wrongly that perhaps the author had resorted to the same tactic.

This oversight meant in my prior studies (which looked at the ability of the Jade Eagle to represent the orbits of the planets and how the angles might represent the names of the planets only the front symmetric side was studied.

Results and Discussion

So, what are the similarities and the angular differences between the two sides. Here the most intriguing observation is 10 out of hte 16 lines are identical. As this paper only looks at the phonetic component, the statistical probability for this to occur is described in a separate paper (see here).

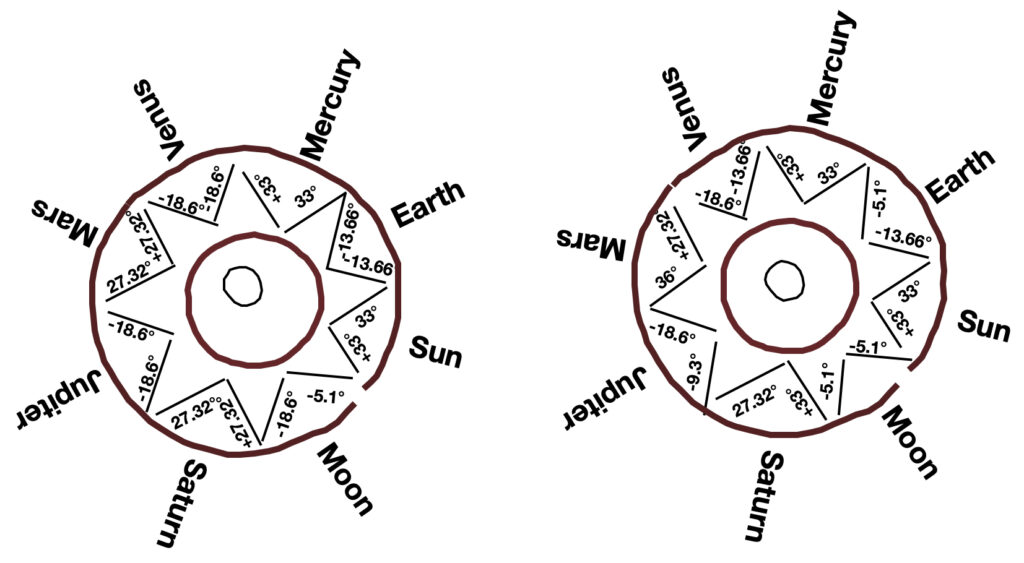

Fig. 1. Comparison of the two sides of the Lingjiatan Jade Eagle. Face 1, on the left, was analysed in my prior studies. Face 2 is the 8-sided star that is found on the rear side of the Jade Eagle. As can be seen, the angles on the reverse side are similar to those on side 1. However, two names appear identical. These being the line-pairs associated with the Sun and Mercury assignments.

The other feature that is interesting following the lines around anti-clockwise, this being the direction that the moon rotates around Earth, in three of the line-pairs it is the second angle that is different (this occurs for Mars, Jupiter, Saturn; and for the line-pairs linked to the Moon and the Earth and Venus it is the first angle that is modified.

The two celestial objects that do not change are the line-pairs representing the Sun and Mercury.

Here it can be argued that Mercury is so close to the sun that the light level does not change much. Venus, and arguably the moon are both closer to the sun than Earth, while the three outer planets are Mars Jupiter and Saturn.

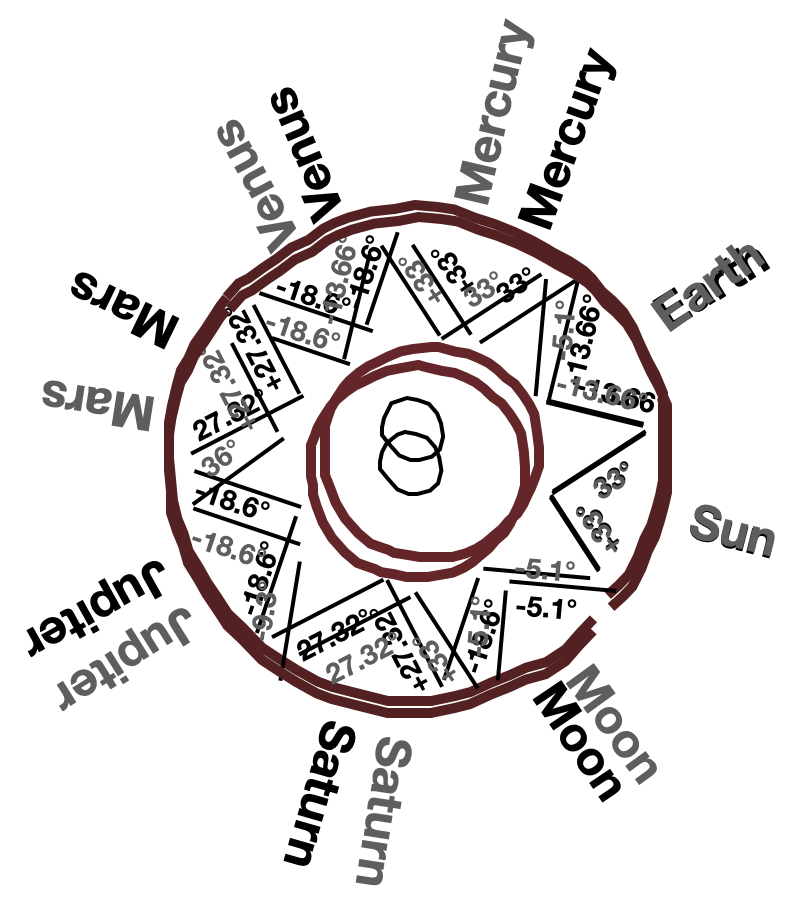

Here there does seem to be a pattern and the pattern could be consistent with the observed changes. An image with the two patterns overlayed is shown in Fig. 2, and it can be seen that the hole is not central.

Fig. 2. Data replotted with the two 8-sided stars overlayed upon each other.

The use fo an off-center hole is important, and actually links to the orbits of the planets, and only be accounting for this does the actual orbits of the planets overlap with the structure drawn by this pendant. A short video of how the orbits overlap with this pendant was shown in the previous article, but is replicated here for convenience.

So, the question remains. What does the second side say, or to be more accurate what might this second side be telling us?

With the structure of the lines I no longer think the lines are related entirely to the waxing and the waning phases of the moon and the planets. I think the closeness of the planets to the sun is more important, and the lines are somehow linked to their understanding of the nature of the different objects.

For example, Venus forms a pentagram with Earth that is created by noting when Venus comes closest to Earth during the planets rotations around the sun; and a pentagram is related to the angle 72 degrees, which is 18 degrees offset from the the vertical and the horizontal axes. This being the angles used to represent Venus in the Jade Eagle – see “The Babel Texts” for further details surrounding the assignments used in the pendant.

The common angles used for Venus and Jupiter is also worth noting.

Though this overlap was noted when I first wrote “The Babel Texts” at that time I was working on so many other problems I did not fully research it. However, here there is a another overlap. Venus and Jupiter are the two brightest planets in the night sky, when they are close to each other.

In addition, the time that it takes Venus to travel around the Sun is 224.7 days, and Jupiter takes 11.86 years. It also takes about 1.60 years. for Venus to appear in the same place in the night sky and Jupiter takes about 1.09 years. This means after Venus and Jupiter are seen together in the sky, it will about 3.20 years later for Venus to return to the same position and 3.27 years for Jupiter. Thus conjunctions of Venus and Jupiter thus occurs at regular intervals, about about every 40 months or so (3 years and circa 4 months)., which is interesting This 40 sidereal-month period might be the explanation for the mysterious 40 degree line, that appears in the later-generation geometric texts. The next conjunction between Jupiter and Venus will occur on August the 12th 2025, and the next conjunction between Mars and Saturn will occur on Wednesday, the 10th of April, 2024.

Looking now at the phonetic elements, within the current phonetic model, the words on the front side are believed to be the names of the planets, and as they are almost all symmetric the names are GeGo (The Earth); ShyiShyu (Mercury); Ish(o)?Ishe (Venus); NuNi (Mars); IsheIsh(o)? (Jupiter); NiNu (Saturn); Ish(o)?Hes (The Moon) and ShyuShyi (The Sun).

These names were based on the early Egyptian name for the moon and Venus; but when compared to the names extracted from Akkadian texts only the Sun can be considered comparable, with Samas being somewhat similar to Shyu-Shyi. Here Samas could be derived from Shya-(Ma)-Shy or something similar. And that is the closest overlap that can be obtained. This argument also applies to the opposite side of the pendant, where the word Agni for Mars just might overlap with the pendant, which creates the word Nu-??, but once more the Akkadian and Mesopotamian texts do not give any consistent results.

In many ways, this is very difficult task, and it will remain a difficult task. This is because the text first appears in archaeological records over 300,000 years ago, and some sites might be as old as 400,000 years old. When you look at modern languages, and note how quickly words change. That is why, in prior studies, the analysis concentrated on comparing the angles present in these lines with surviving linear languages, such a Ogham, where the phonetic components can still be reconstructed.

References

- Derek Cunningham, The Babel Texts, Kindle Books, Independently published.

- Mathieu Ossendrijver, Weather Prediction in Babylonia, Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History, 2021, https://doi.org/10.1515/janeh-2020-0009 Translation slightly modified from Hunger 1976b

- David Frawley, Planets in the Vedic Literature, Indian Journal of History of Science, 29(4), 1994.

- Subhash Kak (https://www.ece.lsu.edu/kak/vena.pdf).

- Huang, Xiaoman; and Wang, Cheng, Interpretation of the Image of Lingjiatan Jade Eagle, Art and Performance Letters (2021) 2: 31-38, DOI: 10.23977/artpl.2021.22005,